Back From The Dead

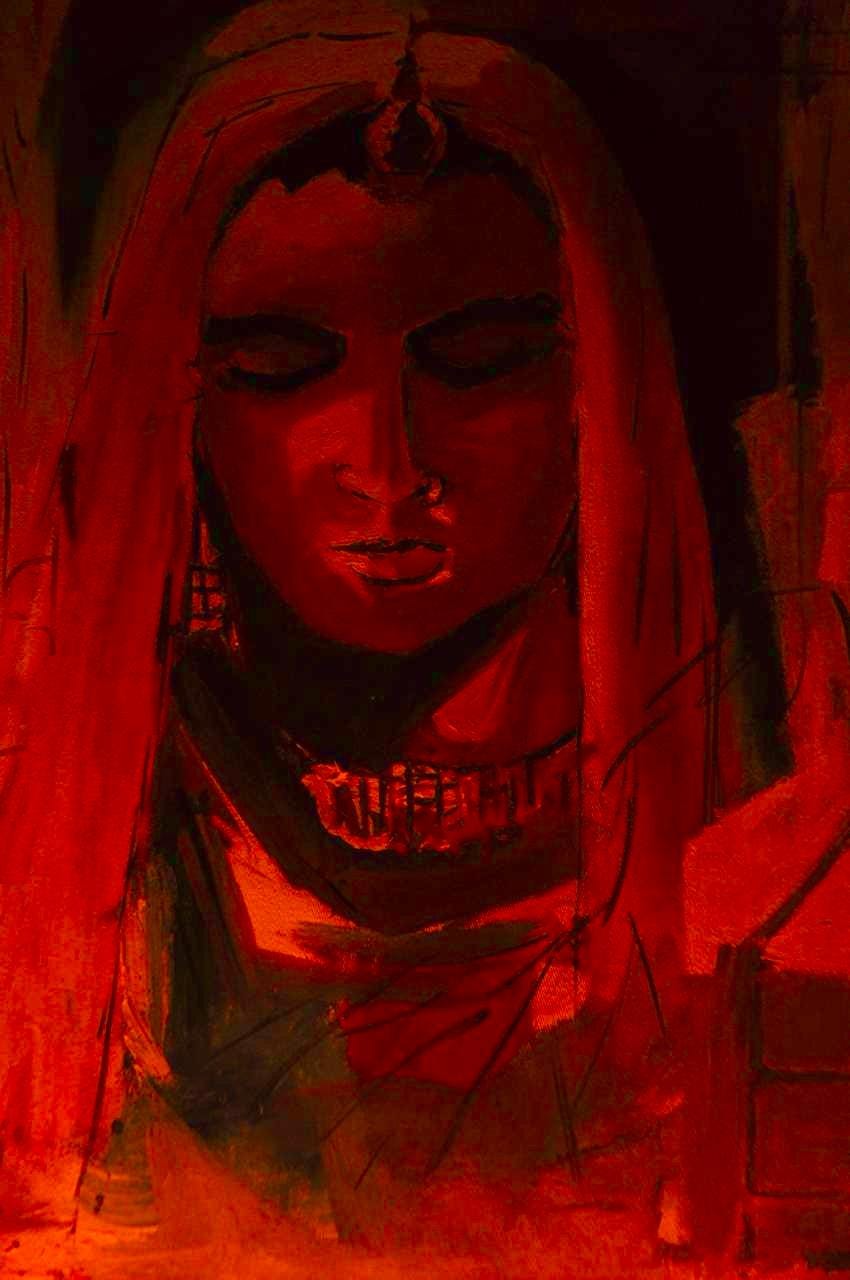

You know how there are some people who you can never forget. And how these people put your life into perspective. Sultana Begum is one such person.

I met Sultana in 2017. I could never forget her face, her words, or her courage. She beat death and fate worse than death to turn around her life and become a beacon of hope for battered women. This is her story. (TW: It is brave but it is certainly not pretty!)

2017

“It’s been 17 years and I can still taste the blood.” Sultana tells me.

We are in the courtyard of the Shaheen Resource Centre in Baqshi Bazaar in Hyderabad. There is a lot of back and forth on the timeline but it all makes sense.

2000

He walked in with a stone. A big stone. He was furious at her. She just wanted him to go to work.

It had been less than a day that he had brought her back from her brother’s house. He had sex with her. She never once mentions love. She cooked for him. He got her a glass of milk. She had just finished it and she casually asked him about his work.

The last things she remembers is being hit on the head twice (at least), blood on her face, in her mouth and on the walls, and falling on the ground. She also remembers hearing herself cry for help but she couldn’t have. The heavily pregnant Sultana Begum had passed out the moment she fell.

When she woke up 21 days later, she was in a general ward of a government hospital in Hyderabad. Her head and face were bandaged. Sultana had slipped into a coma soon after the assault. Her neighbours had rushed her to the hospital.

2017

“It was the eighth month of my pregnancy. My child was safe, Alhamdulillah! What I didn’t know then was the full extent of my injuries.” She continues.

2000

The police spoke to her. Arrested the husband. But then they said it was a ‘personal matter’ between husband and wife. There was no chargesheet, so they let him go.

In towns and cities, stories like these often pique the interest of the media. At least they did back then. They wanted to speak to her. She was a ‘victim’ of violence. The term ‘survivor’ wasn’t common parlance then.

It was during one of these moments that she overheard a doctor tell a reporter, in the corridor, that she will need more time. “She doesn’t know everything, yet”.

Sultana immediately picked up the case file hanging from the footboard of the bed.

2017

Sultana’s voice was calm. Reassuring, even. Her calmness belies her past but her face is a constant reminder of the assault.

“After I had passed out on the floor of the house, my husband got a kitchen knife and slashed my nose and mouth, repeatedly.” This last attack left her disfigured.

According to the case file, she had lost a lot of blood and she needed skin grafting.

1999

She had just turned 18. She agreed to marry a tailor from Warangal—she was told he was some sort of a fashion designer.

Sultana and her three siblings grew up in an abusive family. Her father abused her mother; she passed away when they were little. Her father remarried and left the four children with the grandparents and uncle. He almost completely abandoned his three daughters. With the son, he maintained a modicum of a relationship.

His second marriage bore him three sons and one daughter. The girls were sent to government schools, while the boys went to English medium schools. Sultana resented the discrimination but she made the most of whatever chances she got.

Her older sister was married off at 14. This, too, was an abusive marriage. Sultana refused to get married at 14 and follow in her older sister’s footsteps. Instead, she gave tuitions to pay her fees through school.

When she turned 18, her uncle no longer wanted to keep her at home and her father threatened to stop her allowance. She only agreed to marry because she was promised college.

2017

“They said, ‘our culture is different’. He said, ‘Our women don’t cross the dehleez’.”

There was no college.

1999

With no college in sight, she started helping her husband at their tailoring shop and he stopped working. The abuses began—the beatings, the forced sex, the demand for money.

She did find an ally in her sister-in-law who helped her with money. But for the most part, she was on her own. Whenever she went back to her family for a few days, she was always doled out the usual spiel— “ladki mayake se doli mein jati hai aur uski arthi hi sasural se aati hai”.

She had nearly left on an arthi that day in 2000.

2000

The doctors told her it was a complicated case. The skin grafting surgery was due, and so was her delivery. They didn’t want to take any chances. “You should call someone from your family”.

No one came to meet Sultana at the hospital. No one—not her three siblings, not her father, not her sister-in-law—no one.

The doctors offered to support her if she wanted to file a complaint with the police. But at that time, the safe delivery of her child was her only priority.

She was shifted to a maternity hospital. Once again, she was asked about her family.

She told them “I have relatives but no one will come. All I remember is that I was assaulted and all I know is that I need my baby to be safe”.

The hospital insisted. “You have to sign a form. If something happens to you, who should be held responsible?”

She said. “Please write my husband’s name. He is responsible for my condition”.

She made a final request before being wheeled into the operation theatre. “Save my child. Save me if possible. I want to talk to the police afterwards.”

Sultana gave birth to a baby boy. A week went by and no one from her family turned up. The doctors spoke to a few reporters. Her story was published in the papers.

2017

“When they learnt it was a boy, the family started turning up.” She refused to go with either side of the family. With her facial surgery due, she was referred back to the general hospital. She stayed there for a month, took care of her child, and got herself treated.

“After a month, my brother came, apologised, and took me home.”

The neighbours went bonkers on her first day in her brother’s house.

They called her a bad influence. Instead of backing Sultana who was nearly stoned to death and her face disfigured beyond repair, they made her the villain of the piece.

“They said, ‘Itni neech aurat hai ki uskey shauhar ne iska naak kaat diya!’”

“‘If she is here, our girls will learn to raise their voice, demand their rights and eventually be beaten up. She cannot stay here,’ they said. They fought with my brother.”

2000

Her brother buckled. Sultana took her baby and walked out of his house but she had nowhere to go.

The only place she could think of was the government hospital. She went back and pleaded with the nurses and doctors—who had taken care of her for nearly a couple of months—to let her stay in the hospital. They let her.

For the next seven months, the government hospital in Hyderabad was her address. She helped the nurses and did odd jobs for them. Her son was taken care of by the faculty.

2017

“Though I worked in the hospital, I faced a lot of ridicule because of my face. I was ragged. People got scared. Uncomfortable, even. They didn’t want to deal with me, they didn’t want me near them.”

Sultana has told her story so many times and to so many people, that she rattles off her past in a monotone. She doesn’t miss a single detail and she doesn’t let those details affect her. She doesn’t even skip the part where she attempted suicide. Thrice.

“I thought I could leave my son behind in the care of the doctors and nurses. He would grow up in the hospital.”

2001

Jameela Nishat ran an organisation, Shaheen Resource Centre, out of Baqshi Bazar in Old Hyderabad. She was also friends with the school principal where Sultana had briefly taught while she was completing school.

Jameela met Sultana at the hospital. That was the turning point.

2017

“Jameela apa was the first to tell me I was brave and strong and that I had to live for my child.”

2001-2003

Jameela got her a sewing machine. She spoke to Sultana’s brother, who once again agreed to keep her. Sultana sewed and contributed to the income of the family. This time around, the neighbours didn’t go bonkers.

When her son turned three, she wanted to admit him to a good school. And for which she needed more money. Once again, she met Jameela apa.

2017

“She took me in. There were trainings of all kinds, but most importantly, there was legal help for survivors of domestic violence. For women like me. Battered, broken, bruised.”

This was the spark she needed to get the fire going. She decided to pursue her case and filed a chargesheet.

2003 onwards

Not only did her father refuse to stand by her, he chided her brother for supporting her. Once again, the same old jibe—“she is going to spoil your wife too”— was thrown at him.

Her sister-in-law (husband’s sister) stepped up to back Sultana. She visited the Centre with her and liked what she saw. She liked how Sultana was taking control of her life.

2017

“Visits to the police station were unnerving. They said, ‘I must have slept with another man. Why didn’t I come immediately after the incident?’”

There is a smirk in her tone. “It was their mistake. Back then, they didn’t take my statement properly. He was let go within a few days of his arrest. Later, he ran away to Mumbai and married another woman.”

She filed cases of attempt to murder, cheating, and domestic violence against the husband. The sister-in-law paid for the lawyer. He was arrested. She demanded maintenance. He had to pay up.

2014

The trajectories of the two lives were so disparate now that it was hard to imagine they were ever on the same path.

The husband was in jail when his health deteriorated. He died within a week of falling ill. She saw him for the last time at the hospital morgue to confirm his identity. To be sure.

Sultana, on the other hand, had become a counsellor in Shaheen. She was being recognised and felicitated for her work. She was traveling to countries like the US and Bangladesh, talking about her work, and soaking up every bit of knowledge on tackling domestic violence. She made that trip to the US all by herself!

2017

Her son turned 17. “When we went to the court for hearing for the first time, he was only seven. He was worried. Scared, actually.”

2010

He was nine when he was kidnapped by his father. At this point, after getting him back, Sultana filed for custody and put him in a hostel.

When he was 10, she brought him with her to the Centre during one of the training sessions. It was a session on gender discourse. What struck him the most was the session on the roles of father and mother.

A week later, at the custody hearing the judge asked him, “What is your mother’s name?”

“Sultana Begum.” He said.

What settled the matter, however, was his answer to the next question.

“What is your father’s name?”

“Sultana Begum.”

Some bits of this story is there in the book Beyond Charity. I met Sultana while researching for this book. A version of this story also appeared in She Shines (Short stories by women of Indian origin). You can know more about Shaheen Resource Centre, here.

Wow. What a tale. We demand so much from women . Glad she turned it around.

And the gorgeous book. I am yet to reach this chapter but can't wait to finish it

Amazing story and amazing writing, Savvy